Douglas Yeo

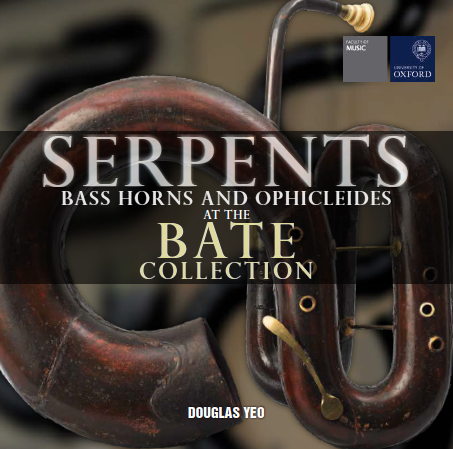

Serpents Bass Horns and Ophicleides: at the Bate Collection

Serpents Bass Horns and Ophicleides: at the Bate Collection

Watford, , United Kingdom

Publisher: University of Oxford

Date of Publication: 2019

URL: http://www.global.oup.com

Language: English

Illustrated. Hard-cover book. 43 pages.

Primary Genre: Study Material - book

Serpents Bass Horns and Ophicleides: at the Bate Collection

Serpents Bass Horns and Ophicleides: at the Bate CollectionWatford, , United Kingdom

Publisher: University of Oxford

Date of Publication: 2019

URL: http://www.global.oup.com

Language: English

Illustrated. Hard-cover book. 43 pages.

Primary Genre: Study Material - book

The trombone, as we all know, has enjoyed an extremely rich history. Spanning nearly six-hundred years, this history echoes with musical ensembles that have joined the trombone with nearly every other known instrument. Along the way, it has benefited from the company of such low-brass comrades as the serpent, bass horn, and ophicleide, which, sadly, have not had such an extended lifespan, but which have nonetheless been integral in shaping the development of the low-brass family (think Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, for example). While these instruments had largely fallen into obscurity, they are being brought back into public awareness by many passionate, skilled performers interested in reviving the sounds of the past through historical performance practices. Among them is former Boston Symphony Orchestra bass trombonist, ophicleidist and serpentist, Douglas Yeo. As one part of a series about the wonderful world of the Bate Collection, Oxford University’s treasure trove of musical instruments, Yeo brings the museum’s unique family of antique low-brass instruments to the greater public in Serpents, Bass Horns, and Ophicleides at the Bate Collection. Beginning with the foreword, marvelously crafted by Dr. Craig Kridel, a fellow champion and specialist of serpent and bass horn, we are invited into the world of these curious instruments. Kridel contextualizes the collection and whets the reader’s appetite for Yeo’s writing, which combines “the public’s curiosity, the enthusiast’s love, the performer’s insight and the scholar’s analytical perspective” (p.5) to inform and dazzle us. Yeo not only converses in all of these voices, in turn, in combination, or all at once, but speaks to readers on each of these levels, from the uninitiated, discovering these extraordinary instruments for the first time, to connoisseurs. Kridel’s dubbing Yeo a “raconteur” could not be more appropriate: Yeo’s wonderfully charming anecdotes entertain while they inform. Accompanied by a variety of images which depict the instruments across paintings, cartoons, and photographs, he recounts and revives the histories of the serpent, bass horn, and ophicleide, breathing renewed life into these instruments. Yeo begins by taking us through the early history of the serpent as a church instrument originating in France or Italy, its function, its construction, and physical position as held by a player. Historical accounts tell us that it could sound just as poorly as it could sound well and be used to great effect, where a mention of “well-documented feats of technical prowess” (p.10) on the instrument leaves us desirous of at least one example. The next chapter goes on to explain the serpent’s arrival in England and its adoption into opera orchestras and chamber ensembles from the late seventeenth century, as is evident from English scores. The instrument made its way into military bands by the fourth quarter of the eighteenth century, when players (and instruments) were imported from Germany. Yeo discusses distinguishing features of English serpents, developed by local makers following the arrival of continental specimens, and further mechanical additions that aimed at improving the instrument’s idiosyncrasies of (often squirrely) intonation. These additions ultimately led to it becoming largely obsolete over the course of the nineteenth century, however, in favor of variants that were increasingly made with metal, from the upright serpent to the bass horn and the ophicleide. Yeo gives details about the development of these newer instruments in the two chapters that follow: the desire for a more “astonishing and powerful bass” (Louis Alexandre Frichot, 1799, qtd. p.20), in addition to an instrument that was more ergonomically viable, led to the upright serpent, or basson russe, in France, constructed of wood and brass, and the English bass horn, made entirely of brass. This last point was a big draw for players and composers alike, catching the eye and ear of Felix Mendelssohn, in particular, who was attracted to it because of its deep, alluring sound and amused by its “[looking] like a watering can” (p.21). The height of the serpent’s development, however, was achieved in the ophicleide, literally a “keyed serpent” (p.25). This technologically advanced serpent was more flexible in pitch, outfitted with one or two tuning slides, and ensured more stable intonation, with the precise placement of padded keys of particular sizes all along the instrument, completely replacing finger holes. It served as the preferred bass instrument in orchestras across Europe through the mid-nineteenth century and, when in the proper hands, proved itself to be quite nimble as a solo instrument. Having traced the history and development of the serpent family, including important information on the modern revival of these instruments (“Postscript: The Modern Revival,” pp.28-31), Yeo goes on to provide specific descriptions of each serpent, bass horn, and ophicleide (and unique variants in between, such as the “ophimonocleide” and the “hibernicon”) housed in the Bate Collection across forty pages brimming with technical information, insightful observations, and detailed photographs. He helps us see these instruments through the watchful eyes of an expert, pointing out what to look for in the way of various types of building materials used for the instruments and mouthpieces; innovations in instrument design by different makers, including shape for acoustical or ergonomic improvement, the addition of keys and tuning mechanisms, and other ornamental, yet functional, appurtenances; certain types of bell flare, brace, bocal, or accessory for removing water condensation; damage and restoration; or the extraordinary provenance or history of a given instrument. While reiterating some points from the first half of the volume, here Yeo invites us to see finer points in much greater detail as we leaf from one instrument of the collection to another. Following these pages, we find a “checklist” of the instruments with makers’ names, dates and places of manufacture, and any distinguishing physical features, such as number of keys or braces, or any damage and repair. Finally, we are given a helpful list of sources for further reading. Yet for those of us interested in pursuing these instruments and their histories more seriously, joining the ranks of those mentioned in the “Postscript,” the one comment we may offer is that Yeo provide a few more resources, in addition to his well-curated reading list, to help us become more thoroughly acquainted with the low brass of a bygone era. What recordings might one look for in order to hear an ensemble that uses these instruments with historical performance practices in mind? For those who seek a more hands-on experience, which contemporary instrument builders might we contact to procure a reliable, historically faithful instrument? Which method books, new or old, could help us in our endeavors? Finally, for the historians, what are some of the sources for the narrative episodes he shares–––where, for example, might we find descriptions of some of those “well-documented feats of technical prowess”? These minor critiques aside, Yeo’s guidebook to the Bate’s collection of serpents, bass horns, and ophicleides certainly accords with the museum’s mission of wanting to preserve artifacts of the past and educate through hands-on investigation. After reading through these tantalizingly vivid pages, it is all but impossible to keep from hopping on an airplane and going to explore the collection in person.